Content warning for pet death.

On Saturday afternoon, my husband and I went to the supermarket. When we returned, our oldest dog, Chance, was suddenly blind.

It was a shock. We spent a little over four hours at the emergency vet to learn that yes, he was blind, no, they didn’t know why, and that he’d likely be blind the rest of his life.

None of us including the vet knew that “the rest of his life” would end Sunday, but Chance continued to collapse overnight and by morning it was obvious that if we didn’t take the compassionate route he’d be taking the other road, and meeting at the same place in either case.

I miss my boy. We’d been together since he was 9 weeks old — fifteen years — and while there were many days that I threatened to sell him to the next band of wandering hobos for peeing on my sofa, I wouldn’t have given him up for the world.

Sunday afternoon I got an email from Home Again, a company that helps to connect lost pets with their owners. You put in the dog’s information and microchip number, and your information as owner, and it’s stored in a database somewhere. If the dog is found and turned into a vet or animal welfare location, they can scan the microchip, look it up, and give the vet your address and phone number so you can be notified that the dog was found.

Home Again wanted to remind me that Chance and Kaylee’s memberships were approaching renewal. I needed to go into the site and shut Chance’s profile down so I didn’t get auto-charged. Good so far.

I navigated to his profile, and shut off his auto-renewal. Then I went back into the profile and chose to close it.

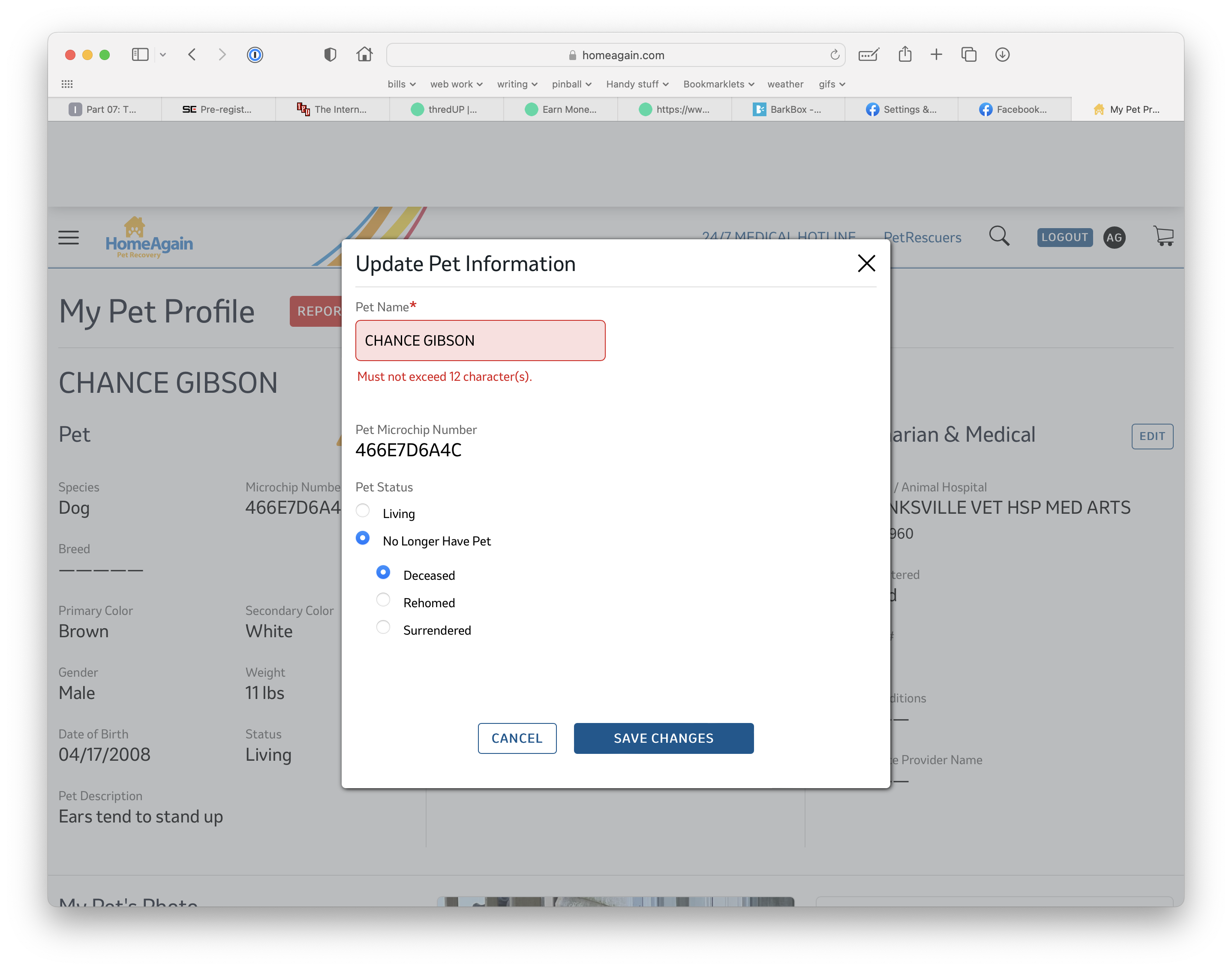

That’s when I hit this:

Chance had been Chance Gibson since the day we brought him home. He’d been Chance Gibson in Home Again’s system since the day we signed him up. But sometime in the last 15 years, someone had restructured a database, or miscommunicated a requirement.

The last thing that I needed in that moment was to tell me that the name of my best bud for the last 15 years wasn’t good enough and had to be changed.

(Bonus salt in the wound for making the text field visually large enough that his true full name, Chance Benedict Gibson, would’ve fit fine.)

Clearly his name *could* be 13 characters because it already was, as evidenced by the fact that it displayed on his profile page. And while I can understand the desire to use the same page for both name and status, disabling a profile would’ve been an OK time to shut off name editing. When the user indicates that they no longer have the dog, it’s a fantastic scenario for waiving length requirements and just accepting the dog’s name.

No one on the other side of the user experience set out to hurt me that day.

But somewhere between when the use case was written and Sunday afternoon, multiple people forgot that if I’m changing my dog’s status to “deceased”, “rehomed”, or “surrendered”, I am going to be hurting like hell.

It didn’t have to be this way.

“User is raw” is a valid use case all its own.