As a Speculative Fiction professional writer, I am treated more professionally by science fiction and fantasy publication markets than I am by UX Design conferences.

I’m certainly not the only one to talk about the subject of UX Design speaking fees in the past few months. Jenny Sheng wrote a thorough post on her experiences speaking in 2018. Vitaly Friedman wrote “Don’t Pay to Speak at Commercial Events” for Smashing Magazine not long after. And Dylan Wilbanks wrote a pretty thorough outline of the actual expenses of speaking as part of his post “The End of Speaking” right here on The Interconnected.

We know we have a problem.

As we are an industry heavily shaped by Mike Montiero’s seminal talk, Fuck You Pay Me, we also know that it’s our responsibility as UX Professionals to ensure we’re treated like professionals. Nobody’s going to do it for us.

So we’re going to look at how a similar industry — speculative fiction — provides both an ethical framework and a template for submission and expectation of professional conferences through the lens of Yog’s Law.

It’s all about the sandwiches

I’m a speculative fiction writer because I enjoy getting paid to write speculative fiction. Similarly, I’m a UX Designer because I enjoy getting paid to design user experiences. If I’m not doing UX Design for my boss, I prefer to be paid for whatever UX-related work I am doing, because it’s probably not as enjoyable as being paid for UX Design.

Or to put it more bluntly, my day job pays me in money, which I exchange for tasty tasty sandwiches. Without the money, regardless of how fun UX is, there are no sandwiches. If given the choice between doing fun things that don’t provide sandwich money and fun things that do also provide sandwich money, I’m picking the fun sandwich-providing things.

An Event Apart and Confab, as conferences, both recognize these facts. They both not only pay their speakers but pay their speakers’ travel expenses, and have done so since their conferences began. They recognize that the professionalism of presenting a conference is a two-way street: speakers deserve to be treated as professionals being taken away from sandwich-providing jobs and compensated for the time and effort they’re putting into their presentations.

Most UX conferences are set up as if we were academics, required by our sandwich-providing jobs to publish or perish. These conferences lack transparency around speaker payment and speaker agreements, often because if we could see up-front what we’re getting, we wouldn’t bother submitting at all.

For example, The Information Architecture Conference (formerly known as the IA Summit) lists extensive information about what they are looking for in a good proposal, topics that are particularly interesting, session lengths, and resources for writing a good proposal. I’m using the IAC here as an example because their speaker requirements are available online even when they’re not open for submissions, but my experience submitting for conferences indicates that this is the norm—in fact, when it comes to providing “what we want” detail, the IAC goes above and beyond (in a good way).

If I contrast this with a good Speculative Fiction market like Beneath Ceaseless Skies, I see a lot of the same kinds of information: what they’re looking for in stories, content lengths, and resources for how to present a good submission.

I also see a section that details editing policies, payment rates and types, who holds what rights to the content after publication and for how long, and response times. (We don’t even talk about the publication rights to our content in the UX world. We treat it as if everything is open-source. Our employers don’t treat their content as if everything is open-source.)

I can tell as soon as I read a fiction market’s site whether they align to SFWA and industry standards for payment and rights, what I’ll be giving, and what I’ll be getting.

That level of transparency is critical. It’s the difference between knowing that I’ll make $240 on a piece of work and I’ll be removing it from the market for a year and knowing that I’ll be making $15 for the same piece and I’ve accidentally given away rights in perpetuity.

And that’s not to say that conferences don’t tell me what I’ll get paid. My experience is that they do, when they send my acceptance notice. As a speaker I get a nice long email that outlines everything they expect from me and when and what I’ll be compensated and sometimes a contract to sign and maybe some other details and oh can I have everything returned by the end of the week so that if I’ve declined they can move to the next person in line?

As UX Designers, we know it’s harder to make important decisions when someone’s put us on the clock. Yet we allow our conference organizers to do it to us all the time. How many people have felt pressured to financially overextend themselves to speak at a conference because they didn’t know the expenses up front? How many people have decided not to submit at all because they couldn’t estimate the expenses and didn’t want the pressure? I don’t know, but I’m pretty sure that the people most affected have voices and stories that aren’t represented in many of today’s conferences.

For my efforts as a writer I earn about $240 per short story I sell, and about $30 per poem. I’m about as successful at submitting fiction as I am at submitting talks, which is to say I get rejected a whole lot, and I expect to be rejected a whole lot. (Some time in the future I’ll write about how rejection isn’t your fault.)

For my efforts as a speaker I’ve been paid “thanks for coming” to “here’s a free ticket to an event that you have to attend for 3 days because we’ve got you slotted into multiple time slots”. I’ve had local events that, when time and expenses were figured in, actually paid me better than professional conferences. And only a local-ish event has ever offered me travel compensation.

So why is the Speculative Fiction industry so much better at telling me how many sandwiches I’m getting out of a professional relationship than Non-Academic UX Conference Industry?

Yog’s Law

James D. Macdonald is a science fiction author. He’s written 35 novels (most with Debra Doyle) and he’s obviously successful. I didn’t learn about Mr. Macdonald through his writing, though. I learned about him through his vigilant work to educate novice authors (like me) about literary scams.

Mr. Macdonald coined Yog’s Law:

Yog’s Law: Money should flow toward the author.

Yog’s Law is a heuristic for gauging whether you want to have a professional relationship with another organization (or person) in speculative fiction publishing, and it’s been quoted by many professional authors, editors, and others in the field.

The longer version of Yog’s Law would be something like:

Be wary of deals where the publisher charges a reading fee, or a submission fee, or an entry fee, or a publishing fee. (Self-publishing has made that one a bit more complicated, but vanity publishers who charge you to publish your book are still the biggest problem.) Be wary of editing fees, research fees, or anything else where you’re putting money out up front in return for the potential opportunity to make money in the future.

Taken at a more strategic level, Yog’s Law is an ethical framework. An ethical speculative fiction publisher is one whose goals are aligned with the author: write and publish the best work available so that people are willing to read, buy, and talk about it. An unethical publisher is one who a) doesn’t pay professional rates for professional work, b) doesn’t disclose their rates, fees, and other expenses and/or c) takes money from the author for their product instead of paying the author for their product.

Which way is the money flowing now?

It’s 2019. Seven-year-olds are getting paid on Youtube to review toys, for pete’s sake. There is no conceivable reason why any of us, no matter how skilled or unskilled a speaker we are, should be paid nothing—or worse, should pay out money in travel or lodging—for creating and presenting content at a conference. Even if all you spend is an hour of your time to create the presentation, that hour has value.

For local small-scale events, it’s fair and equitable to speak for free if you choose to do so. A local event can be a great place to test a talk or workshop for a larger audience, it can help grow your local network, and it often is a labor of love where local companies and organizations are donating time so that our industry can grow organically.

There’s a big difference between the local monthly chat in someone’s donated conference room and a professional conference. Some of our conferences charge $2000 for a 3-day event ticket with hundreds of attendees and then turn around and claim they can’t pay their speakers. (One event I went to asked me to speak “as part of a panel”, and then after I accepted clarified that to attend the panel I’d have to pay the $250 workshop fee “to rent the space and cover food”.)

When your entertainment is sponsored, your conference has sponsors, your food is middle of the road, your staff are volunteers, and your speakers are receiving a conference ticket or less in compensation, one tends to wonder what you are doing with the money.

Recently a self-described conference organizer attempted to justify this behavior in a conversation on Twitter by explaining:

The conference organizers are either 1) not very good at turning a profit and probably aren’t charging enough, or 2) are focused on making a profit, and going to pay speakers that attract an audience (and sell tickets).

If you aren’t getting an offer to get paid, they’ve made a judgement call that your name isn’t big enough to sell tickets. Simple as that.

In other words, there’s no intention to pay content creators and presenters. Our current ethical framework is based on unprofessionalism:

- Some conference organizers are too unprofessional to make money and can’t pay you.

- The rest are too unprofessional to pay you, unless you’ve spent so many years “building your brand” at your own expense that they can exploit that brand to make themselves more money.

Well that’s a ringing endorsement from the industry.

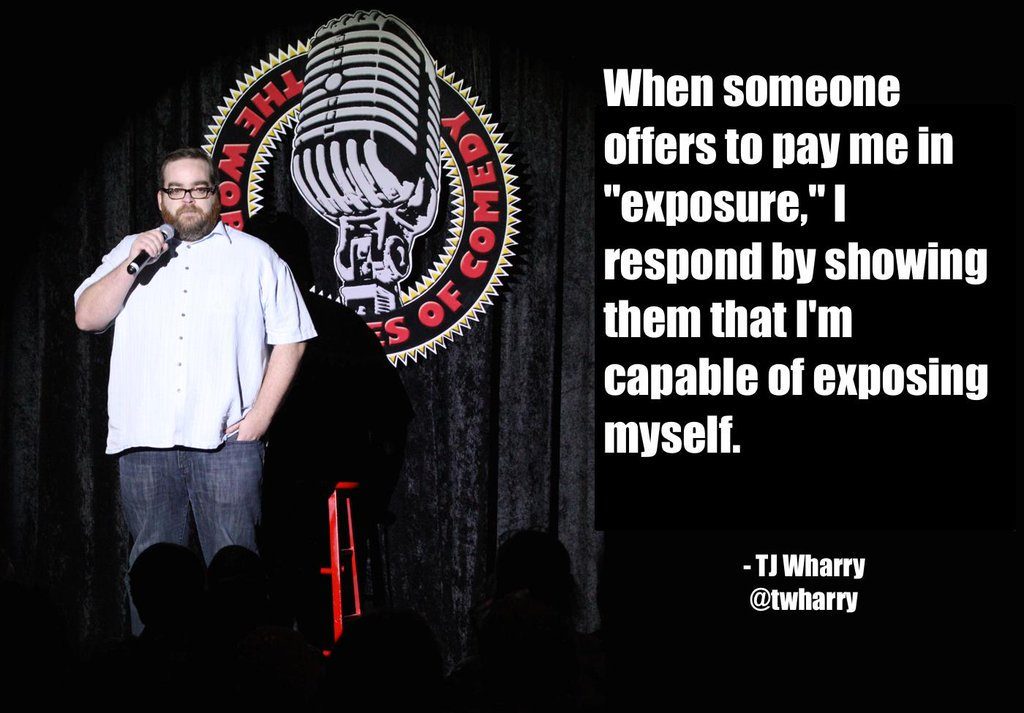

The exposure argument

There are the folks that argue that by providing free labor to a possibly-competent possibly-exploitative conference organization we’re gaining back what we give in “exposure”.

I could give you a dozen reasons why that’s obviously false, from the fact that conferences aren’t built around landing gigs to the fact that we don’t accept the exposure argument for spec work, but really it sums up to this:

No matter what part of any creative industry we’re talking about, whether it’s fiction, UX, speaking, juggling, whatever, “exposure” never results in the cash necessary to buy tasty, tasty sandwiches.

A Yog’s Law for UX

The practice of not paying speakers is exclusionary; it means only people who can afford to pay their way through the process have the opportunity to speak. It sets a horrible example to our employers and clients when we devalue our own work inside the industry. It’s also at minimum exploitative and in worst cases predatory; speakers are expected to produce content and perform for conference organizers who are often using an opaque call for papers to describe the payment for services.

And it has to stop. We can’t have the bulk of our continuing education system in this industry be driven by only the subset of “people who can afford to teach” when there are so many other, arguably more diverse, arguably more interesting ideas available.

Yog’s Law shows us a clear path to resolve many of these issues:

Money flows toward the content creator.

We expect payment for our wireframes, our deliverables, our research, our design sprints, our thought leadership. We turn down spec work. We fight against huge “design exercises” during hiring practices. We expect to be paid in every corner of the industry except speaking.

So it’s time for the industry to realign to Yog’s Law.

- Speakers should be paid.

- That pay should include a ticket for the conference.

- It should include travel and expenses.

- It should include a stipend for the day.

- It should at minimum outline the content rights for whatever you present if it’s being recorded, and consider paying you if that material will be used in some kind of ongoing fashion.

Because we have value, because we’re good at what we do, because we respect our own work, because we want others to respect our work, and because italian hoagies are still not free, our ideas and our presentation of those ideas cost money.

Caveat Emptor. Buyer beware. When we’re buying our own work, the money is flowing the wrong way.