In my last two posts, I wrote about how much I hate designing filters (because I never get the time and data to get it right) and the things I’ve learned about filters to make them better (even if I’m not fully confident in their necessity).

And I told you all that so that you’d understand filters in general and why some filters are just nope. That’s right, we’re finally getting to the bit I meant to tell you in the first place.

At the time of this writing, I’m planning a trip to ReplayFX for the Pinburgh pinball tournament in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (By the time you read this, the event will probably be over, because the other two articles are so freaking long.)

During my hunt for all the stuff that one requires to ship two adults to Pittsburgh for a week I decided I wanted to try packing cubes. I don’t know anything about packing cubes so I’m a hesitant consumer. I’m not sure what criteria I should be looking for, I’m sort of just eyeballing sizes, and I’m reading a lot of sketchy website blogs about the glories of packing cubes coincidentally published and or funded by packing cube companies.

Since I’d recently had a good experience with a luggage website called eBags, I gave them another shot.

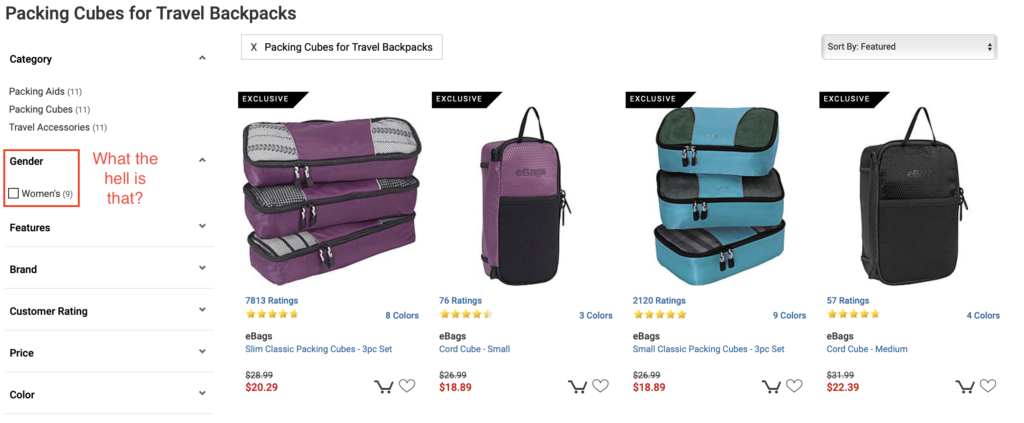

So, strong top navigation to get to travel accessories, a nice mega-menu that includes packing cubes, and a four-category filter that helps me break down the 127 choices to a manageable 11 that will fit in a backpack.

And then I spot it.

The gender filter.

Now I’m trying to be honest and fair about the world even though I’m generally a raging feminist, because there are things like clothing that eBags sells that can definitely be sorted by gender. A woman’s jacket is cut very differently from a man.

It’s also true that when it comes to transporting things, there are places where products that both men and women could use are designed in such a way that men are more likely to use one and women the other. Women’s handbags are called purses or and men’s handbags are called messenger bags. Women’s laptop totes tend to be styled to look like very large purses, and men’s laptop totes are still messenger bags.

So, like, different. As long as you ignore that some men might like a tasteful women’s laptop tote, many women I know prefer messenger bags, the luggage really can’t be told apart one way or the other unless “creamsicle” is somehow only for women, and there are way way more categorizations for humans and their style preferences than the two genders of “women” and men”.

But here we are and this is a thing.

Maybe I would yield to the argument that “our research indicates that primarily women or only women are purchasing packing cubes” since I am a woman, and I am buying packing cubes, and the only people I hear talking about packing cubes are women, and I don’t have the site’s actual purchasing and marketing statistics.

Except, well, two of the packing cubes are missing from the “women’s” count.

This brought up all kinds of questions in my mind.

- Which two products were not women’s packing cubes?

- Was there something special about them?

- Why couldn’t I simply identify the non-women’s packing cubes when I didn’t have the filter checked? Why did the non-women’s packing cubes look like the women’s packing cubes?

- It’s 2019 just what the actual hell?

I hunted down the suspect packing cubes and discovered that they were single-pack and two-packs of a full set of packing cubes. The women were being offered the three-pack and four-pack of that exact same product.

Being me, I punched the little “chat” button on the screen and asked. That conversation went down something like this:

Edited for length and clarity, and to protect the representative, who doesn’t need to get shit about this…

11:59:45 [rep] Hello, this is [rep], and I will be assisting you today.

12:00:05 [me] Hi! I have a question about the packing cubes for travel backpacks

12:00:35 [me] When I first load the page there are eleven options, but if I choose the gender of “women’s” the number of results drops to 9

12:01:11 [me] So what makes the single hyper-light packing cube and the two-pack of the same cubes inappropriate for women?

12:02:08 [rep] Packing cubes is a unisex version, seems there should be an glitch on the filter. I’ll report this to our IT team for further review.

12:02:33 [me] You can let them know that unless they’re loaded with testosterone supplements or tampons, packing cubes don’t have a gender and the entire filter should be removed for this category because it’s 2019 🙂 thank you!

12:03:18 [rep] You’re welcome!

Frankly, the eBags representative was fully professional in this entire exchange and while I haven’t seen a change yet, at least I felt like I was heard.

But this is a design problem. It’s a content strategy problem. At some point someone with design and architecture chops should have been involved in determining what filters were appropriate for what products. The filters that display on each of the major (and most of the minor) product pages throughout the architecture differ in presence and order, so the excuse isn’t that the same set of filters are being applied to all products.

And even if the decision of whether a filter appears is driven by “did the sales person stick it in the metadata when they loaded it into the system?” major categories where filters absolutely cannot apply should, well, not have that category available for tagging products.

You shouldn’t be able to tag a “shoe size” on the luggage, for example. It just doesn’t work. They are too big for shoes. Or shoes are too small to carry things. Either way, filter mismatch.

This could seem like a petty little thing to point out, but it actually carries a lot of meaning. To women it infers that we’re the packers and the organizers and the domestics. To men it infers that domestic tasks like packing for the whole family are women’s work. All the folks that identify as genderqueer or nonbinary or ace or trans are erased altogether, which either means they’re cleared from having to buy packing cubes if they don’t want to, or they’re subtly rejected if they do.

Bad filters do damage.

It’s not just gender damage. In a tweet I can’t find now, someone in the disability community recently pointed out that hundreds of restaurants have tagged themselves as having “accessible” locations… but when a wheelchair user arrived for dinner they discovered that “accessible” meant “only one step” or “the busboys will carry you” or “you can take the smelly service elevator up through the kitchen to get to your own birthday party.” That’s not accessible.

Gender, disability, race, and a few others are civil and social model risks, the ones that call out whether our organizations are good citizens or whether they couldn’t find their ethical ass with both hands and a flashlight. They harm people directly at the core of “do we see you as people?”

Beyond those models there are other tangible risks to getting filters wrong:

- financial risks on financial websites, where a user might pick the wrong product without adequate information

- medical risks on doctor’s tools and websites, where a poorly worded, missing, or additional filter could result in the wrong medication for patient or the wrong treatment, or even the wrong doctor availability for an appointment

- science and engineering risks on space flight and bridge building and any number of other tasks where people are looking up parts or specs or blueprints and filters help limit the data to human-understandable ranges

- business risks where a poorly-formed filter set discourages users from getting the information they need to do their task and thus don’t fulfill the business goal

The list goes on, in every industry, in every part of society, in every place that searching or filtering or managing complexity can be found.

So above and beyond everything I wrote about how to decide if you need filters, how to use data to analyze existing filters, how to research with users what new filters to add, what features of filters are effective, and how filters fit in with the larger site architecture, the most important guideline I want to impart to you is this:

If you can’t justify the existence of the filter with actual use cases that do no harm to customers that come from marginalized groups, if you can’t find cases where the filter answers a question that users have actually asked during usability testing, if you can’t find a way that the filter actually adds good to the world, take this critical step:

Delete it. Filter it from your filter list. Make it a non-filter. Nope it back into the hole it stepped out of.

And document the hell out of “why we are not doing that again good god it’s 2019” so your organization learns the skills necessary to think before they filter.