I’ve been doing what we now call User Experience (UX) for over 15 years, from small startups to Mega corps. And in every job, no matter what, I hear some version of this speech:

“Design is too slow! You have this big, heavy process, but we need to ship a solution, yesterday! You want to do user research, but we already know the problems! Why can’t you just tell us what color these pixels should be and stop asking us about users, goals, and outcomes? Where’s your sense of urgency?”

The first ten or so times I heard some version of this speech, I was frustrated. One of the design field’s greatest insecurities is how much we have to explain what we do. Other parts of a company – engineering, marketing, management, the janitorial staff – don’t get asked what they do. It’s just understood. The return on investment is clear, and if it’s not, the benefit to the organization is (or the costs of not having it). With User experience design or product design, it’s often not as clear. So, we will encounter the speech more than once in our careers.

Nowadays, I just expect the speech. I am ready for it. Because it’s not entirely true. Take, for instance, the question of speed. Yes, design can seem slow, especially if you are focused on output and deadlines. It’s one more thing to add to your already tight schedules with razor thin margins for error. The problem arises when you always deliver like that. Are you sure you’re doing the right thing? How much does it cost the business when you do the wrong thing? How do you account for the costs of poor product-market fit? Who’s paying for all the rework?

The Sense of Urgency

Earlier this year I spent way too much on a dinner at The French Laundry, one of the most famous high-end restaurants in the USA. Going to The French Laundry was a big bucket list item for me, so I was really happy to finally get a reservation. While the food was, well, amazing, I spent a lot of time watching the service. There’s an intense flow to how everyone works, from filling glasses to identifying issues to making sure everything is exactly as it’s called out. The way they move, signal, and interact is designed to be the highest class – both the height of luxury and a natural extension of the open social posture of Americans. They’re organized. One table isn’t going hungry while another table has all twelve courses deposited at once.

Thomas Keller, the head chef and owner of The French Laundry, famously has signs in the kitchen and the entry to the dining area reading “Sense of Urgency.” There’s a commitment on the staff to make sure things move. And things do move.

The thing is… their “sense of urgency” feels completely different from the “sense of urgency” we designers often encounter in the tech world. Keller’s team has a clear vision they share and common goals they are trying to achieve. This is a world-class, three-star Michelin restaurant. It may be just a job, but there’s clear ownership of that job. They are urgent because they’re not taking actions for the sake of speed; they’re not doing for the sake of doing.

Pick a Path, Make a Plan

When I lead a design team into an engagement, I focus on creating a shared vision and shared ownership so we can move with that urgency the French Laundry staff demonstrate. We have limited resources and time, so let’s make sure every action we take moves us to understanding the problem, the user, the business goals, and not just taking action for the sake of taking action.

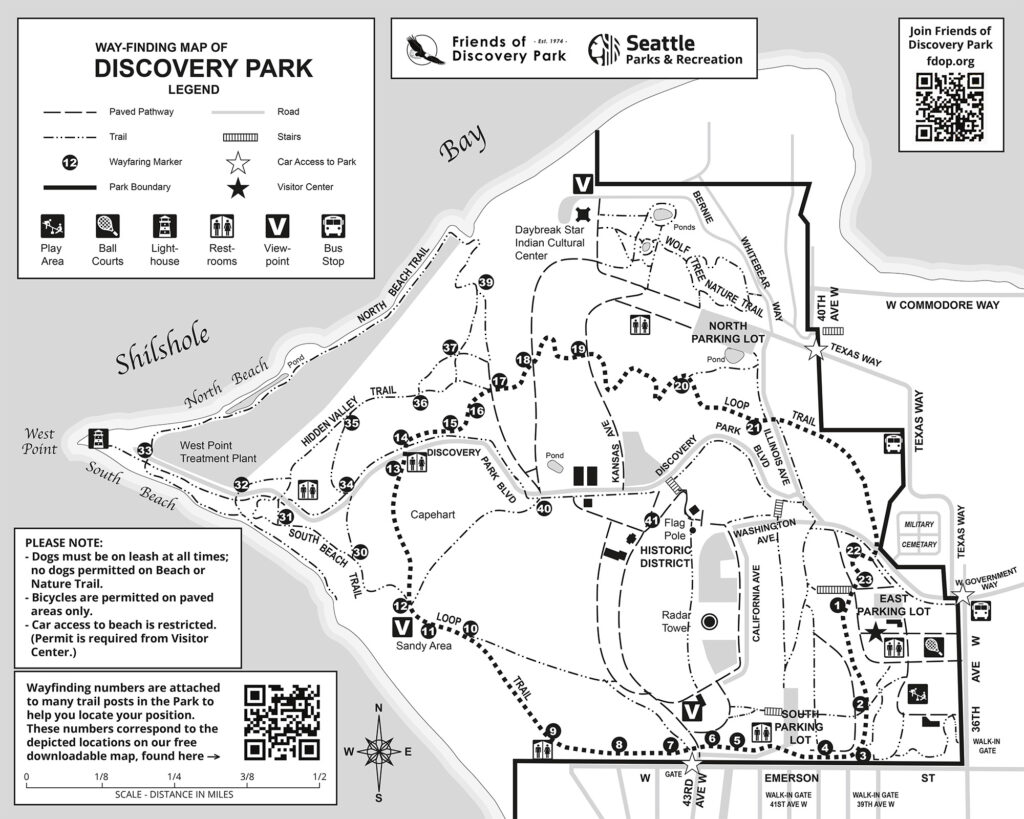

No hiker would ever just walk in a direction without a map hoping they figure out their goal as they go. That’s just a recipe for getting very, very lost and possibly very injured. Instead, they pick a path, make a plan, adjust as needed, and focus on completing the trek. The role of design in the process is to help create a shared vision that everyone on the team can own and be part of, just as you want to get your hiking or climbing group to agree on a path and a plan lest you get lost and/or injured.

In shared vision and ownership, we create a shared organization. For UX to be effective in an organization, you need organization. The best design teams I’ve seen work in (and often create) environments where communications are clear, roles are well defined, and the vision and goals are collectively held. Ideally, these are environments built on trust, where everyone has a voice in the process, and everyone collaborates instead of conflicting.

That’s why we push user research in UX. That’s why we question. That’s why we are constantly pushing ourselves and everyone involved in a project to build and execute on the vision. We’re trying to make sure everyone shares a common understanding. In understanding, there is vision. In vision, there is organization. In organization, there is ownership. And when all this lines up, we move with urgency, and we deliver outputs that match the outcomes we all desire, quicker. We are like those hikers with a plan – we end up on top of the mountain faster, better, and safer.

Designers want to create, innovate, and make things better on every level, so they need strong product leadership, smart engineers, creative program management, and solid, well-communicated vision from the business and leadership to succeed. When they see a lack of any of these things in a situation, they will usually take them on themselves to make them happen. Sometimes, that means designers have to do jobs that don’t fit what you’d expect from a product designer. Sometimes, our jobs look like program managers, making plans and holding people accountable. Sometimes, their jobs look like product managers, to help close the gap between the business and the customer. Sometimes, they make the copies, bring the pastries, present to executives, and manage the conversation, at the same time for the same meeting.

Some of the strongest product managers, engineering leaders, and project managers I’ve known were (or are) senior designers. (Off the top of my head, I count three friends who moved from design to product or marketing and have been wildly successful and have risen to executive roles.)

Sandwich Making

So, what does this pragmatic view of design have to do with that “sense of urgency” at the French Laundry? A well-run design team will focus on creating shared vision and shared understanding so that they can focus on outcomes, not outputs. This doesn’t mean designers blindly follow some process with eleventy steps and gates; after all, the design process is something you learn so you can learn how and where and when to break it. What it means, though, is they need to tailor their process towards the outcomes rather than follow a siren call to chase outputs, overlooking iteration, improvement, and innovation.

Imagine if you’re a trained chef, working in a sandwich shop — not some bespoke gourmet place, but a national chain that sells subs. You would love to make the sandwiches that people really want, ones that stay with them, ones that make their lives better. Instead, they come in for lunch, and they don’t have time for anything other than a fast-food sandwich. So, you splat pre-cut meat and vegetables on bread, lunch break after lunch break. The experience of cooking becomes completely transactional.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/20240305-SEA-HamandCheese-Amanda-Suarez-herojpg-5f7304ba4a7e43018052d2056495c266.jpg)

In organizations driven more by output than outcome, this sort of transactional “sandwich making” is the order of the day for designers (and coders, product managers, developers, and everyone else in the process driven by delivery deadlines.) You’re not really solving the problem; you’re just shoveling designs (or code) to keep things moving down the line.

Transactional organizations do not build great products. They just don’t. All they do is keep slapping half-thought solutions onto problems that may not be solved by said solutions. Sometimes, the sheer volume of output overcomes this, and the company is just fine. Usually, though, they end up drowning in tech debt, experience debt, support debt, and sometimes actual debt. The customer experience team burns out, the marketing team struggles to put a brave face on a messy experience, and the engineering team starts talking about burning down the code base and starting over even with the immense cost and dangers that come with that.

Kinda like they are trying to hike without a map.

Are designers lacking in a “sense of urgency?” Sometimes. Perhaps. But in reality, they’re asking for everyone to get on the same page and deliver the right solution effectively, collaboratively, with the highest benefit to the business and the people who use our products. Designers aren’t trying to slow you down. They’re just trying to keep you from getting lost.

(This was previously published elsewhere under a different title. Thanks to Tope Larayetan for editing the original.)