If you’re a console gamer, you know the drill. You go out and buy a new AAA release for your console, come home, start the game… and download all the patches and bug fixes before you can play it.

(If you’re a console gamer of a certain age you remember when there was no internet and the game companies had to release as bug-free as possible the first time. But I digress.)

Internet in homes is pretty ubiquitous, especially among those who can afford a Nintendo Switch or a Playstation 4 in the first place, so the chances that the person buying the game doesn’t have access is pretty darned low…

…unless you’re in the hospital for a cystic fibrosis tune-up, and only one of the two household Nintendo Switches has copies of Super Mario Party or Mario Kart 8 that are up to date. And the hospital’s guest internet, which is perfectly useful for downloading email and surfing the web, has decided it won’t let you connect to the Nintendo game servers. And driving 45 minutes home just to update the games really isn’t an option.

I doubt Nintendo planned for this specific scenario, seeing how Gen X couples where one member has cystic fibrosis and the other one constantly forgets to keep her Switch up to date are relatively rare. (I hope.)

On the other hand, someone at Nintendo at some point said, “But what if a group of friends want to play and someone’s software isn’t up to date and they can’t jump out onto the internet?”

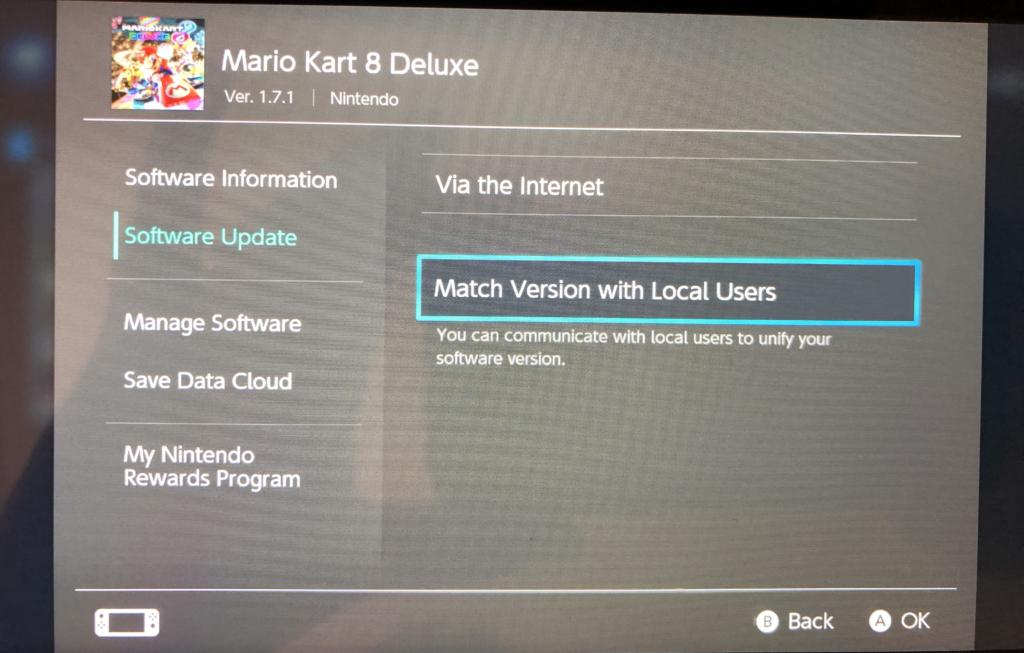

They must have, because both Mario Kart and Super Mario Party had options to locally sync versions.

In other words, I could download the software updates I needed from my husband’s Switch over local wi-fi, even though the internet wasn’t available to me.

This local syncing feature is, based on my software experience, most likely complicated to build, complicated to test, and constantly being regression tested to ensure that it’s not broken. There are a thousand reasons why Nintendo, if trying to save money, could have cut the feature — ranging from the fact that most users generally have internet access available to the often cited “user responsibility” to keep their software up to date. It doesn’t directly make Nintendo more money; it’s not an in-app purchase. It’s an edge case. The vast majority of their users will never need to look for it.

And yet.

My first gaming system was an original Gameboy given to me by my husband for my 18th birthday. When the Final Fantasy franchise moved to the Playstation, my purchasing dollars followed it, and while we’ve always owned Nintendo products, only the Wii Fit series grabbed my attention since the late nineties.

And if you asked me today what the most usable, most accessible, and best console for families of any age was today, I would answer the Nintendo Switch without hesitation and without regret.

In software and in business, we so often discount, neglect, and botch our edge case user scenarios that our users don’t expect to be treated well if they’re even remotely in the range of the Pareto Principle. For that matter, we often abuse the Pareto Principle (otherwise known as the 80/20 rule) so heavily that most business people I talk to think it means “handle 80% of the users’ use cases and ignore 20%” instead of its actual meaning, which is that 20% of the causes are generating 80% of the effects… and that means the last 20% of, say, profit, is all edge cases all the time.

It’s never a bad time to ask whether an odd use case could benefit everyone, and whether your treatment of your users as having complex lives that buck the statistics could be the difference between a disgruntled customer and one that’s loyal for life.