According to my receipts, I’ve been playing Minecraft since about October of 2014. My friend Ken started playing right around the same time. Neither of us play multiplayer (on a server), or with other people. In fact, even though Ken was my roommate for almost a year and a half I think we looked at each other’s Minecraft games maybe five times combined over that time.

Now Ken, he’s been to every kind of biome, and he’s been down into the Nether. He’s caught every kind of animal. He’s farmed mobs. He’s found giant mushrooms and rare metals and log cabins and all kinds of other things.

I have dug holes. I have lined those holes with polished stone, and then I have dug more holes.

Now, one might be thinking that’s the point of Minecraft but here’s the difference between how I play and how Ken plays: Ken digs holes to get resources to go do things with those resources. I dig holes to get resources to organize those resources.

What are Minecraft materials, really, other than content? We’ve got different kinds of content: granite, diorite, andesite, some various ores, sand…

Each of those content types have their own behaviors. Some will stay wherever you put them. Others are affected by gravity. Some are fragile to Creeper explosions and some are more resilient to them. (In that sense, Creepers are essentially online trolls.)

Some content types in Minecraft will kill you if you get buried underneath them. They’re like keeping up with the current news cycle.

Some content types will set you on fire. They are also just like the current news cycle.

Ultimately, what I discovered was that every Minecraft world is like a giant poorly-organized SharePoint intranet site: it has veins of quality content surrounded by unappealing stone that someone piled in there without reason. The goal is clear: dig out the quality content, organize it until it can be used to create greatness, then create greatness.

Y’all, the world of Minecraft is a mess, and I set out to clean it the heck up, underground anyway.

In my first world, I was quite satisfied to dig things up and sort them into boxes.

The problem with that approach was that some of my rooms underground got too big for the system to handle. Instead of displaying the far wall, the system would just draw sky, and I saw some spectacular sunsets from way underground. But hey, it was organized!

So about a year or so into this one, I decided that, while it was nicely organized, it wasn’t organized enough, so I started over in a new world.

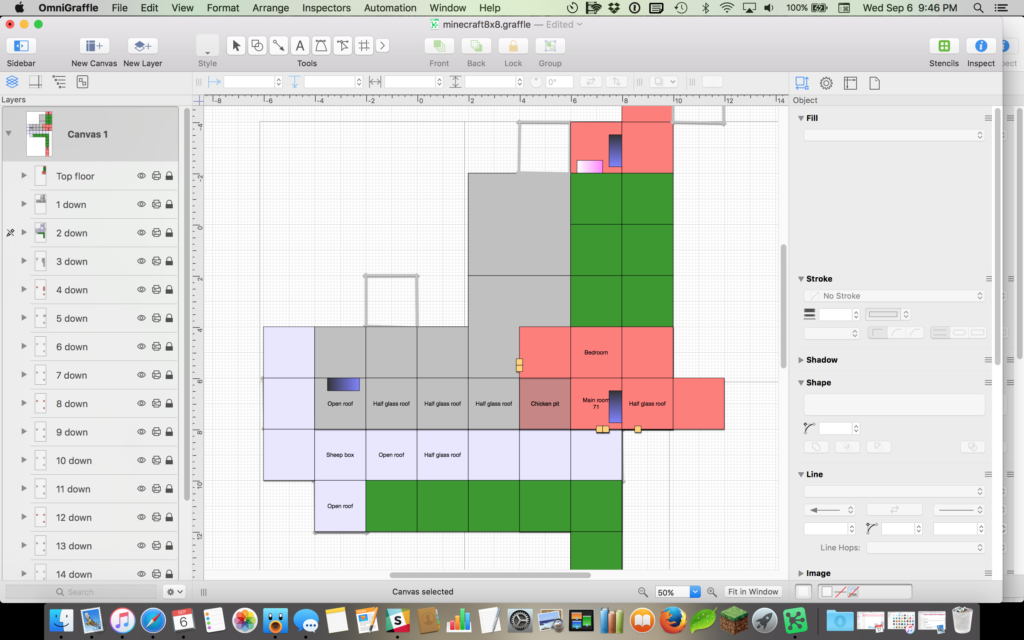

In that one, I decided, I’d keep everything organized and neatly structured. I colored each floor by rock color, and each room was 8 blocks by 8 blocks (10 by 10 if you counted the walls).

And that was all well and good, except (don’t laugh) all the rooms look the same, so I kept getting lost. I turned to Omnigraffle to track my work.

That’s right, in addition to a content strategy for the content I was discovering buried below the grass in my minecraft world, I was now building a site map.

Most people would’ve reconsidered their life choices at this point, but I am not Most People, I am an Information Architect.

Folks, this is what I live for.

The way I relaxed between big projects at Vanguard was by inventorying incredibly large SharePoint sites.

The way I relax in the garage or the kitchen is by reorganizing the cabinets or the wood shop.

The way I relax on my phone is match-three games, or logic puzzles, or Solitaire (which is ultimately just a big sorting exercise).

And apparently, the way I play Minecraft is to organize the world.

We make the world into the things we enjoy, as much as we make what we enjoy into the world. If after a long day of content strategy, what you want to do is organize even more content, Minecraft scratches that itch quite nicely for me — even if it means you don’t play it like most people do.

On the other hand, if you tell me that your favorite thing to do is organize your video game materials into varying boxes, friend, let me introduce you to a career in taxonomy. You’ll be fine.